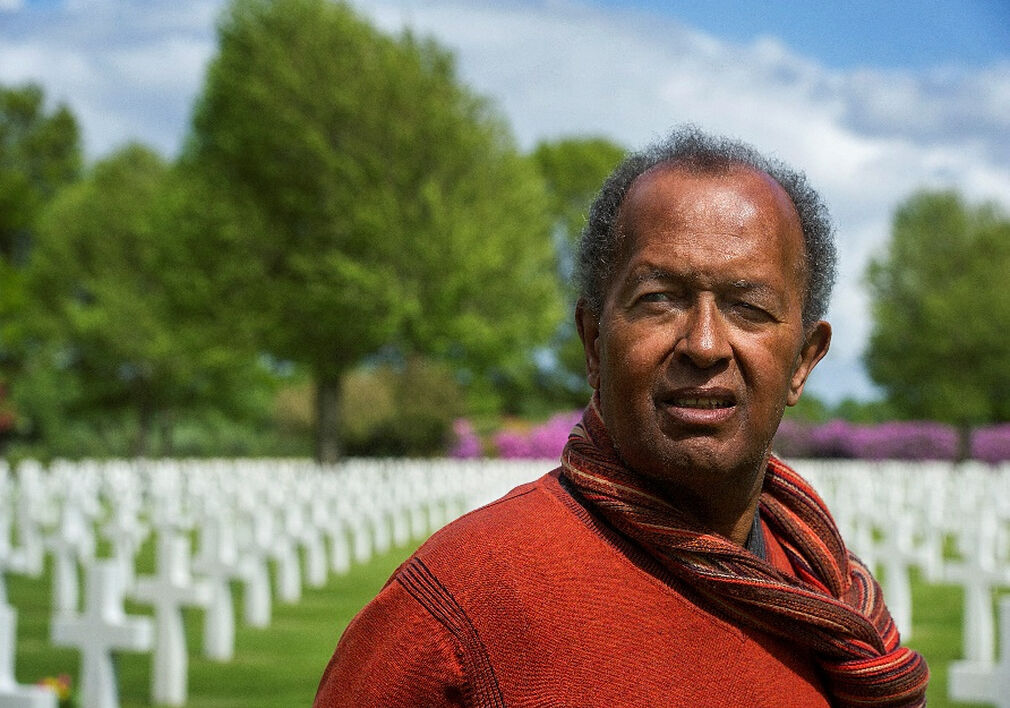

Huub Schepers

Huub adopted a standard answer for all the times people asked about his origins. He said he was from Suriname (a former Dutch colony). He regularly tried to find out something about his biological father. He searched, albeit in vain, in libraries, archives and on the internet for information about the Black soldiers stationed in the Brunssum area at the end of the war. His unknown biological father was one of them.

The boy must disappear before I come home. And if you don't arrange that, I will drown him in a bucket.

On November 5, 2014, he touched on that book during a presentation of the book From Alabama to Margraten. It was the first time he could read about the Black American soldiers stationed in Europe during WWII.

Through Huub, his willpower and his courage, a new reality has arrived for many of his fellow sufferers. He decided in 2014 that with the story about his childhood as a child of a Black liberator, born in the completely white, Catholic province Limburg, he finally had to go outside. Meanwhile a number of other people, also begotten by a Black American soldier, share their past with each other. On December 18, 2015, Huub was one of those present at the first meeting of children of Black liberators who participated in the eponymous oral history project.

The meeting was organized at their own express request. Netty - Huub's ex wife, joined Huub and brought him home afterwards. On the way back he said to her: "I have the feeling that I finally have brothers and sisters."

Huub died not long afterwards, on January 14, 2016. The private farewell service was held on Martin Luther King Day, January 18, 2016. A number of his "brothers and sisters" were present. The American flag he flied every year on the death of M.L. King was half-masted, now draped over his chest.

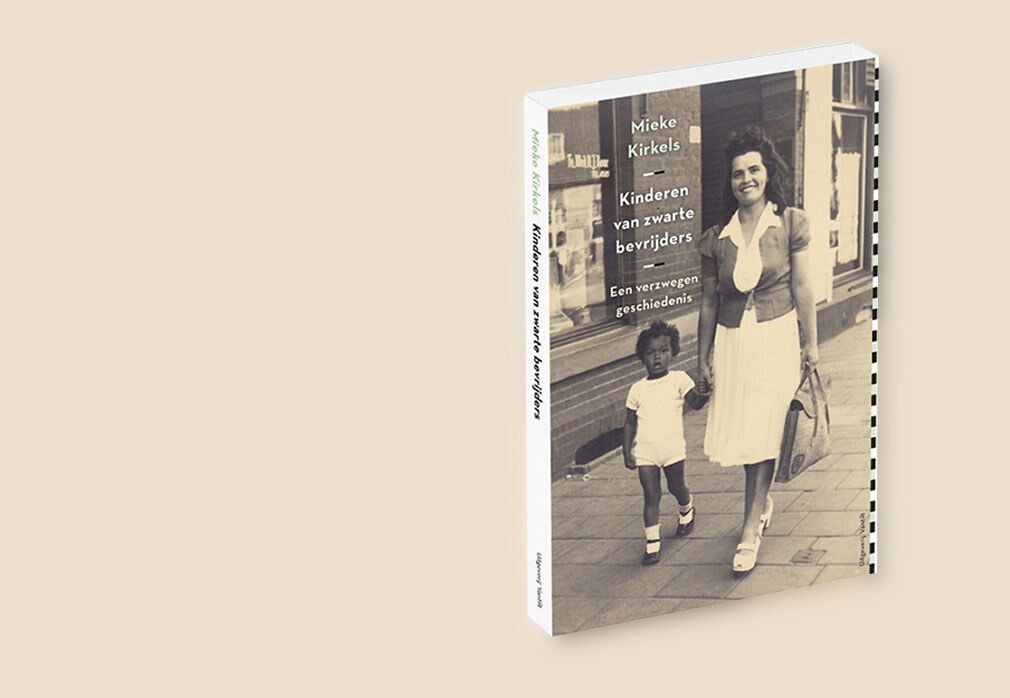

The book "Children of Black Liberators - A Hidden History (Vantilt 2017) is dedicated to Huub Schepers.

Huub has never known his father. He hardly knew his mother either. She apparently dealt with a Black American soldier during the liberation period, while she was already married and had two children.

Her husband, an NSB member, was in custody in Valkenburg during the liberation time because he had been a member of the Waffen-SS. He demanded from his wife that ‘that young must disappear before I come home. And if you don't arrange that," he seems to have threatened," I will drown him in a bucket. When he returned home early, little Huub was already gone.

As a baby, Huub looked unhealthy. His bed was in the basement. Mother did not want the older children to attach themselves to Huub. She never went walking with him out of embarrassment to be seen with him. Her husband's sister occasionally picked up the baby for a walk so that he could get some fresh air.

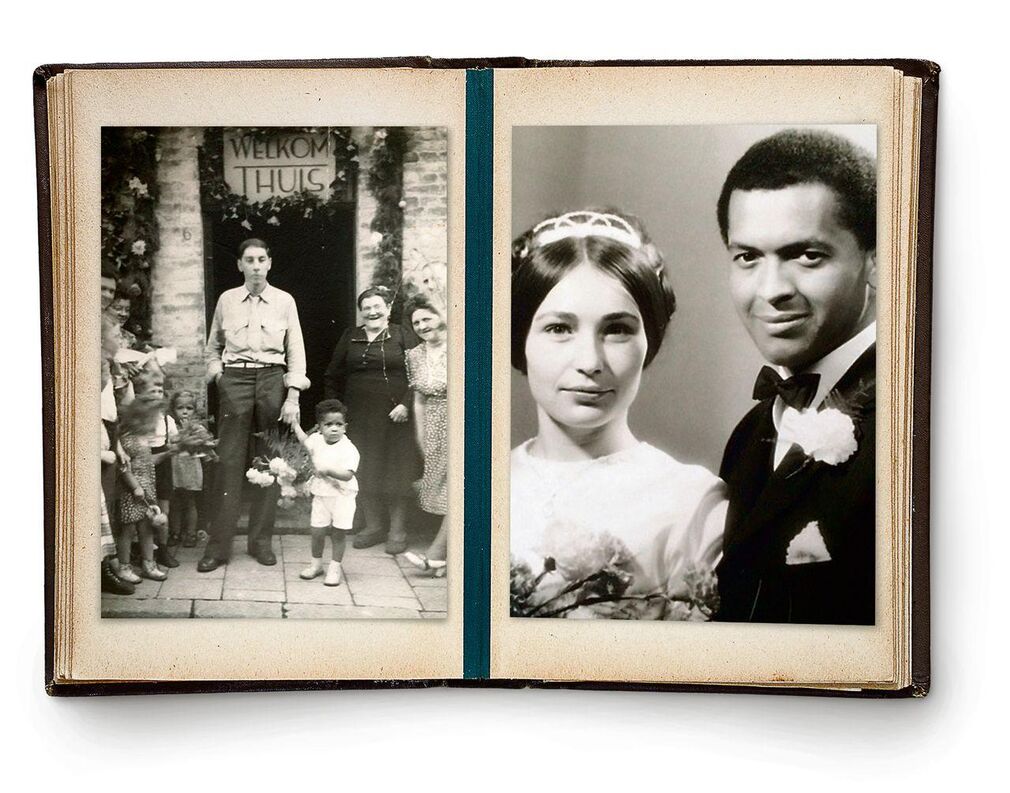

As a child, Huub lived at eight different addresses. The first time he moved, he was eleven months old. Mrs. Renet, an older widow in Sittard, had heard of the malnourished boy who barely left the house and took him home. Huub: "Later, I heard from Mrs. Renet that she mixed milk with water and gave me something to drink to recuperate." She also said that she thoroughly washed him when she first bathed him because of his dark skin.

Mrs. Renet's house has always remembered Huub as a warm, safe environment. At the age of four he was taken away, because the Child Protection Agency disapproved, partly at the insistence of his stepfather, that he grew up with an older woman. He ended up with a family in Landgraaf, but after a year he was taken away again. Huub: "My stepfather was probably behind that again." In a car - presumably from someone from the Child Protection Service - he was driven to Maastricht, to a nuns' children's home in Capucijnenstraat. "Then everything turned black" as Huub called it. He does not remember anything for a long time afterwards.

You felt that something was wrong. The fathers and brothers were totally unpredictable.

The next address where he ended up was Saint Joseph House in Cadier en Keer, a boarding school for the Child Protection, run by fathers of the Sacred Heart. Dozens of other "liberation children" lived in Saint Joseph, children conceived by white American soldiers. But there were also "war children", children of NSBs and German soldiers. In addition to Huub, there were also a few liberation children with a Black American father.

Huub: "You felt that something was wrong. The fathers and brothers were totally unpredictable. Some were hysterical when they beat you. But no-one ever dared to say something about it. Occasionally I was beaten or scolded by one of the brothers for being a son of a whore, for a Black whopper. For punishment, I was once locked up in one of the cachots in the basement. These were small rooms with a box bed, a concrete table and a chair. And a catechism. In the morning the mattress was removed and then you just sat there. With that catechism. "He was punished once he ran away. If you wanted to be one of the big boys, you had to try it at least once. When you pee in your bed, you were locked up in the steel wardrobe for punishment with nothing but a sandwich with salt. Another punishment was that you had to sit on your knees on a balance beam, with your hands up, and then not be allowed to move. The boys were allowed to shower once a week. The crotch of the underpants was checked beforehand. If that wasn't stain-free, you had to take a cold shower. Another punishment Huub remembered: brushing the joints of the tiles with a toothbrush. And he also remembered a group of older boys beating up one of the brothers one day, shouting and shouting: “Don't you dare come back to the children with your feet.” Huub never received visitors and during school holidays he also stayed at the boarding school. "I often longed for my old foster mother, Renet. I felt safe with her. "

'One day, totally unannounced, I had to get into a car with my briefcase.' A brother had apparently questioned the way one of the fellow brothers dealt with Huub. Probably it was discovered that Huub was sexually abused and he had to go to cover it up. 'It was a long car journey, which ended at the Jelgersma clinic in Oegstgeest. I was sixteen at the time'. Huub suspected that his shyness and silence after the abuse were a reason to put him in that institution.

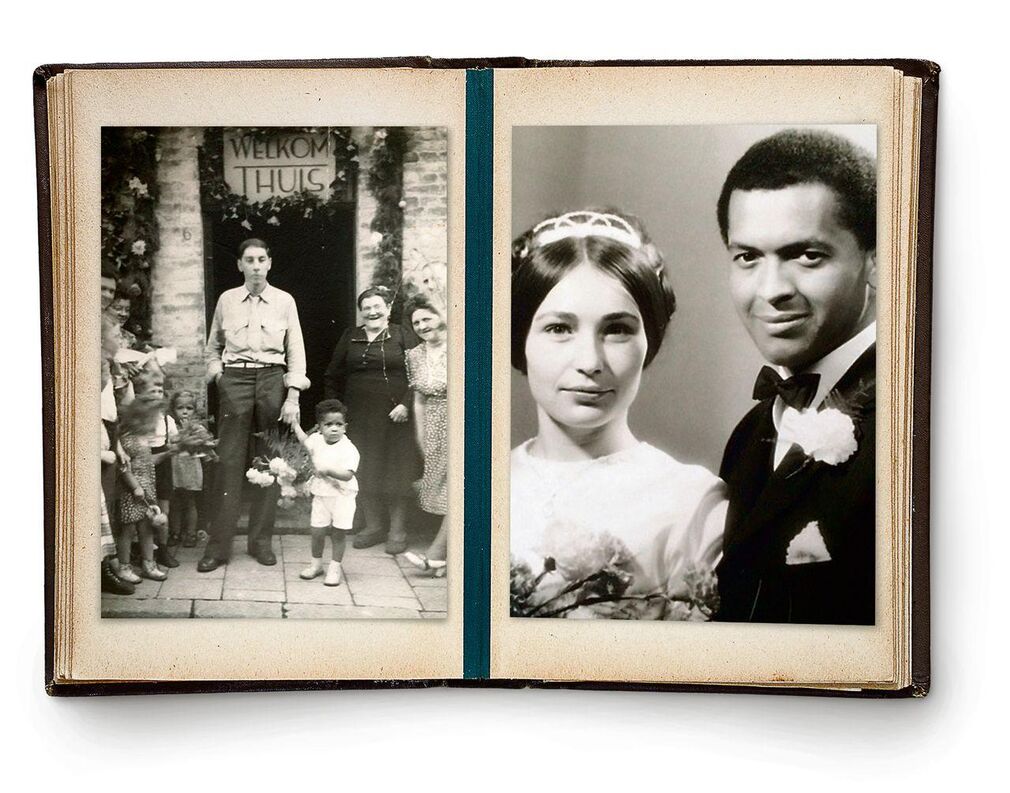

After returning to Saint Joseph, he finished high school. He was then placed in a Catholic nursing home in Hoogcruts to win and work there. In 1964 he met colleague Netty Wanders, a girl from Noorbeek. At the same time they followed a training for nurses. Netty only realized that something special was going on with Huub when she noticed that a woman in the kitchen of the institution occasionally offered him some extras. "He has no family," the woman told her. At Netty's house, she was the oldest of ten, Huub quickly found his place. For the first time he was part of a family. When they married in 1966, Huub got a home for the first time in his life. In a village nearby they went to look at a residential floor and noticed how the owner was shocked to see Huub. The rental was canceled. 'Because,' said the woman, 'something like this is not used here.'

Don't blame me

Before a marriage could take place, however, a problem had to be solved. At that time you could get married without your parents' permission when you were twenty. Huub: "Then I had to contact my mother and stepfather." The Child Protection Agency mediated when stepfather Schepers refused to cooperate. The pastor also had to be involved. He organized a meeting between Huub and his mother. For the first time since his out-of-home placement in 1946, Huub saw her again. His oldest half-sister was present at the meeting. Huub had visited her before, together with Netty. The meeting, to which he had been somewhat pleased - for he finally saw a family member - was bitterly disappointing. Huub: "Of course she has always had to remain silent. When I was taken away as a baby, she was nine and her brother suddenly disappeared. That must not have been easy for her. "When Huub saw his mother back, he couldn't handle his emotions. He burst into sobs. "She didn't cry," he recalled. The only words from her that stayed with him were: "You can't blame me." He thought she was a distant woman and it stayed with that one encounter. When she died and Netty accidentally saw the mourning advertisement in the newspaper, her children were mentioned in it, but Huub did not.

In Huub's adult life, long-term and severe problems arose, as a result of which he could no longer function. In The Netherlands The Deetman Commission was established in 2010 to investigate sexual abuse in Catholic institutions. Then Huub breaks. Little by little he told his wife that it had happened to him. Netty urged Huub to submit a complaint to the committee and then everything that Huub had hidden for so long came out. He fell far away, so far so far, that in the end it took years of therapy to be able to process memories of his time there. Huub's complaint was declared well-founded and compensation followed.

After a new psychological and physical collapse, Huub was admitted to a psycho therapeutic center in 2009 and he and Netty decided to divorce. Living at home was no longer possible, because he could not tolerate anyone around him for long. It was often too full in his head and then he took the bike and drove for hours through the hills. In the last years of his life, Huub, together with his assistance dog, Buddha, lived in a sheltered home in Gulpen. The dog woke him up when he had nightmares. Netty continued to care for him until his death.

In the Volkskrant an extensive article about him appeared at the beginning of 2015, because he thought that people should know his life story. That article was followed by an article in the regional newspaper De Limburger for which he was interviewed together with Ed Moody. One of Huub's half-sisters then furiously called the newspaper editors. Huub called her and informed her that he wanted to meet her. After a long hesitation, she indicated she also wanted that. During the meeting she told him that her father had been a good man and that she had always appreciated that he had Huub put out of the house at the time. "He did that for us," she told Huub. She had never thought about what that meant for the life of her half-brother.

In the same year, Huub met Rosy Peters, another child of a Black liberator. During his long career in nursing, Huub had worked as a psychiatric nurse at the Annadal hospital in Maastricht. 35 years earlier Rosy was nursed in the department where he worked and where she received a lot of support from Huub. Seeing the two again in 2015 was emotional.