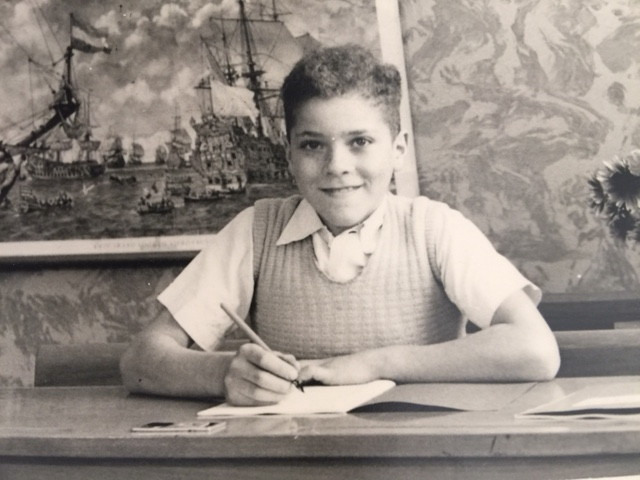

Ed Moody

In September 14, 1944, when the liberators entered Maastricht, four African American soldiers were housed with the Wetzels family on Nieuwstraat in Heer. Mother Lene ruled the household. Her youngest daughter Lenie thought it fantastic that the soldiers had arrived and the family gave them a warm welcome. The soldiers enjoyed being in a comfortable home. The husbands of the three older sisters befriended the soldiers and taught them Dutch card games and how to ride a scooter.

The family also thought it interesting that the soldiers had a different skin color. Except in Catholic mission magazines, you never saw dark-skinned people. The soldiers were equally unfamiliar with a different skin color. Before they left for Europe, they hardly had had any contact with white people. One of them, Edward Moody, was an exception with a black mother and a white father. Ma Wetzels was very fond of Edward. When he came home after his shift ,the first thing he did was sing for Ma. He was a great singer, and had some recordings made in Maastricht, at Bakelite records. Unfortunately, said son Ed, we have not been able to find those records afterwards.

Edward worked as a truck driver for one of the QMSC units. From there, supplies were transported for troops going to Germany. Lenie, 22 years old, fell head over heels in love with Edward, who at the time turned 23. The feeling was mutual and in January 1945, Lenie discovered she was pregnant. They married on February 24, at city hall in Heer. The American military command was not happy. A black soldier who was dating a Dutch girl would be transferred as quickly as possible. It was to be expected that Edward too was transferred. It is not known when he left Heer. After the wedding, Lenie moved to Hasselt in Belgium, to live with uncle Pie.

Edward was to board a troopship to take him back to the US. Uncle Pie took Lenie to Antwerp to say goodbye to Edward but they were unable to see him. Lenie returned to Hasselt and on September 14, 1945, Ed was born in the barracks in the barracks in Roermond.. According to Ed, the birth was free of charge, maybe because through her marriage, his mother had become an American citizen.

Lenie and her son lived with her uncle Pie in Hasselt for a few years, where she had a job as a maternity assistant. Her mother found it difficult to accept Ed. When Ed was 2 years old het met his grandmother for the first time and immediately the ice was broken. When he was 5 the family moved in with the grandmother. Ed's parents kept in touch sporadically during Ed’s childhood with letters and gifts for Ed. In 1951 Edward invited Lenie and their son to the US but due the grandmother’s illness they never went and the contacts between Edward and Lenie faded away.

Transcription of one of Edward's letters to Lenie:

June 19, 1951 Trenton N.Y. Tyler street

Hello little girl,

Well it has been a long time since I heard from you or any of the family so I thought I would drop you a line to find out how you and Eddy are and all the family. Leny, I know I have no right to ask you this, but I hope you will and for me and do this for me what I would like you to so is have a photo made of you and Eddy. Send it to me please.

Well Leny, I don't know what to say so I will ask you a few questions if you don't mind

- Do you have a boyfriend now?

- Can I have Eddy for 2 or 3 months here in America?

- If I send you the money will you come to America? For 2 or 3 months?

- When you answer my letter tell all about yor family, tell me about all mother Bettie, Annie [illegible] Louise and every one. Well this is all until I hear efrom you so please answer soon.

So bye bye, give all my love kiss Eddy for me and I still love you.

P.s. don't forget the photo,

As ever yours

Ed Moody

I never had to keep silent about my origin. I didn't do anything wrong, did I? Why wouldn't I be able to talk about that?

For a long time, Lenie was not interested in another relationship but when she met another man, wanted to marry him. As she was officially married to Edward, she needed to divorce him. The officials were unable to trace him so after a while he was declared missing and a divorce was possible. As a young boy, Ed did not miss knowing his biological father. He never had any trouble because of his skin color. Sometimes his friends jokingly called him 'the red Negro', since his curly hair was reddish. But missing a father? No, not really. Ed: 'We always had uncles visiting.' He looked back on a happy childhood.

Later on, he found it interesting to have an American liberator for a father. 'I never had to keep silent about my origin. I didn't do anything wrong, did I? Why wouldn't I be able to talk about that?' He remembered only one comment about his ancestry. 'I can't believe you just tell everybody your dad was a soldier. You got guts!' he was told by somebody whose father was a German soldier. Ed realized he was not the only one with an unknown biological father.

In 1959 he started a band with his friend Hub Kuijpers called The Music Boys, then All Sounds which performed in the local area. Performance abroad were difficult meant as he needed to request a day pass from the military police, because he did not have a passport. That changed after his marriage to Annie Grothues.

Now I regretted I did not start looking sooner, this was so final.

Annie and Ed got married on June 24, 1967. For future children, it was important for Ed to officially become Dutch. The paperwork was completed in time for the birth of their son Richard in 1967. A daughter Esther was born in 1968. As a Dutch citizen Ed was eligible for military service but obtained an exemption as he was the breadwinner for his family and mother-in-law Ed worked as an upholsterer and as a building materials representative and encountered little prejudice. 'On the contrary', he said, 'I benefitted from my unusual last name. Introducing myself as Moody was a great conversation starter in my work as a representative, because people would often ask questions about that.'

Later his daughter Esther searched the internet for information about her grandpa to surprise her father on his fortieth birthday. Ed was not interested in this and thought it not necessary. 'But,' he admitted, 'for a long time I secretly hoped he himself would be looking for me. After all, he was aware of my existence, wasn't he?' On the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation Esther decided to look again and found an address and telephone number in New Jersey. Esther called. A woman called Bessy answered and when Esther said,'I am calling from the Netherlands.' Bessy knew. She had always known Edward had a son in the Netherlands. But Edward had passed away.

Ed: 'Now I regretted I did not start looking sooner, this was so final.'

Thanks to Esther they know something about Edward. After his return to the US in 1945, he worked as a driver. He was good at his job judging by an award for 500,000 kilometers of damage-free driving. Ed got in touch with Debbie, Bessy’s daughter, Edward’s stepdaughter. From her, Ed learned he had a half-brother and a half- sister. His half-brother died when he was 27, and all they knew about his half-sister, Mia, was that she lived with her grandmother, who lived to be 102. Debbie was living Bermuda and for years, she and Ed’s family maintained a good relationship. They made plans to meet in England. But just like Lenie’s trip to America, as a young mother with her small son, this trip too was canceled at the last minute. The last thing they heard from Debbie was that she was seriously ill.

In 2014, Ed read the memoirs of Jefferson Wiggins, the African American grave-digger from Margraten. Ed was shocked. For the first time in his life, he learned about the racial segregation in the American army, where his father had served. Ed: ‘How is it possible we never heard anything about that?’ A short while later, he saw the article in de Volkskrant in which Huub Schepers spoke about his life as a liberation child. Ed got in touch with Huub. They liked being able to share their experiences. As it happened, Huub lived in Sint Joseph for a number of years, which was the crisis center where Ed used to work towards the end of his career. Huub was placed there by child protection services. They exchanged information about the basement pens, the ‘prison cells’ where children were put on a bread-and-water punishment regime by the Fathers.

Ed: 'When I was working there, I often thought certainly horrible things must have taken place in those cells.’

By then Ed and Annie had five grandchildren. They never had to ask Ed about his origin, because they grew up hearing stories about their grandfather in America. ‘My children and grandchildren are proud to have an American grandpa,’ Ed said. With his grandsons Milan and Jordi, he regularly visits the American cemetery in Margraten. And then they take a moment to look at the grave of Jacob G. Moody from Arkansas. Ed adopted his grave, and decided to go and look for information on his namesake, who was a white soldier.