Henry Vanlandingham

Henry grew up in a family in Buffalo, New York. Before he left for Europe in 1942, he worked as an aircraft engineer for a while. He was married to Mary. In 1943 they had a daughter, Arzeymah.

Henry worked as an aircraft engineer for a while. His son Philip was born in 1946, after Henri's return from Europe.

Vanlandingham was stationed in the Limburg village of Berg for more than two months during the Limburg liberation period. He worked as a technician and driver for the so called Red Ball Express unit. That was a gigantic supply operation that drove back and forth between the port of Antwerp and Liège / Aachen, to supply the American forces that were about to cross the border with Germany.

During his stay in Berg, Henri became friends with Trinette Nols-Weusten. When his unit received a new assignment, he left Berg.

After the war, Henri had his own construction company, until he became inspector and coordinator of the maintenance of buildings in the Buffalo municipality. Henry and Mary divorced in 1967. Later Henry remarried Hazel, a teacher from Georgia. They later moved to Silver Springs, Florida.

50 years later, Henri’s Dutch grandson Marc traced him in the US. Henri then heard for the first time that his girlfriend of the time had given birth to a child of his. He invited his daughter Els to come to the US. From the day of their first meeting, father and daughter and their families have developed a special bond. A bond that also continued after the death of Els (2004) and Henri (2006).

https://nos.nl/uitzending/8540-nos-journaal.html

From the diary of Henri Vanlandingham about his time in Limburg.

“This old car moans like a woman giving birth. The truck never runs smoothly, even on paved roads. I know I can't keep up with the convoy, but there's nothing you can do about it. " But always when I am almost in "The Berg", it seems as if the truck from itself is going to drive faster and flies on its way home, like a runaway horse that is almost broken.

Charlie woke up twenty miles earlier and asked where we were. I told him to go to bed again. He always seems to feel good when I get tired. But I always like to drive these last few miles myself.

Because of the trees in the area, I cannot see the spire of the church of "the Berg" against the hills of Maastricht. But as soon as I see it, I know it's only five minutes to my point. Charlie is my favorite co-pilot en route. That boy is really black, with those big glittering eyes looking at you. He grew up in Cleveland in much the same way as I did in Buffalo. Poor, but always determined to find a way to become something other than someone who works in the fields, like all colored boys. But the war destroyed all our plans.

Now we are both here in Holland without any idea when and how we will get home again. I have been living in "The Berg" for about two months now. And that now feels more like home than Harlon Street (in Buffalo, MK).

This old cart moans like a woman giving birth. The truck never runs smoothly, even on paved roads

I can't even remember Mary's face the way I was used to. Instead, I only see those Dutch scrubbed faces.

Home is so far away that it seems unreal. We have gradually stopped talking about home. I know it's not good to feel at home in such a place as here, because as soon as you do that, the army leaves again and you make sure you don't care.

It's time to wake up Charlie and see what he has for our shop this time. The last ride I had a lot of fun about it. Before we report to the depot in Valkenburg, we stop at the cave and hand over things to Frans. Frans is a bad boy, a tall, thin guy, smart and big enough to hold on to the prize he has in mind.

He set up a shop in the cave and sells his business daily. Many of the villagers also come to listen to the radio. He hid it there when the Germans prohibited possession of a radio. In the beginning I advised Frans what he could ask for the things, but now I don't have to tell him anything anymore.

Our bosses know everything about the black market operation, even though they pretend they know nothing. They know that the Germans have taken away all their cattle from the farmers and stolen their harvest. Some of the men from the village have even been sent to Germany as forced laborers. When we arrived, we saw how much effort the women had to make to feed their children.

The bosses know that the disappearance of small parts of the stock keeps the village alive.

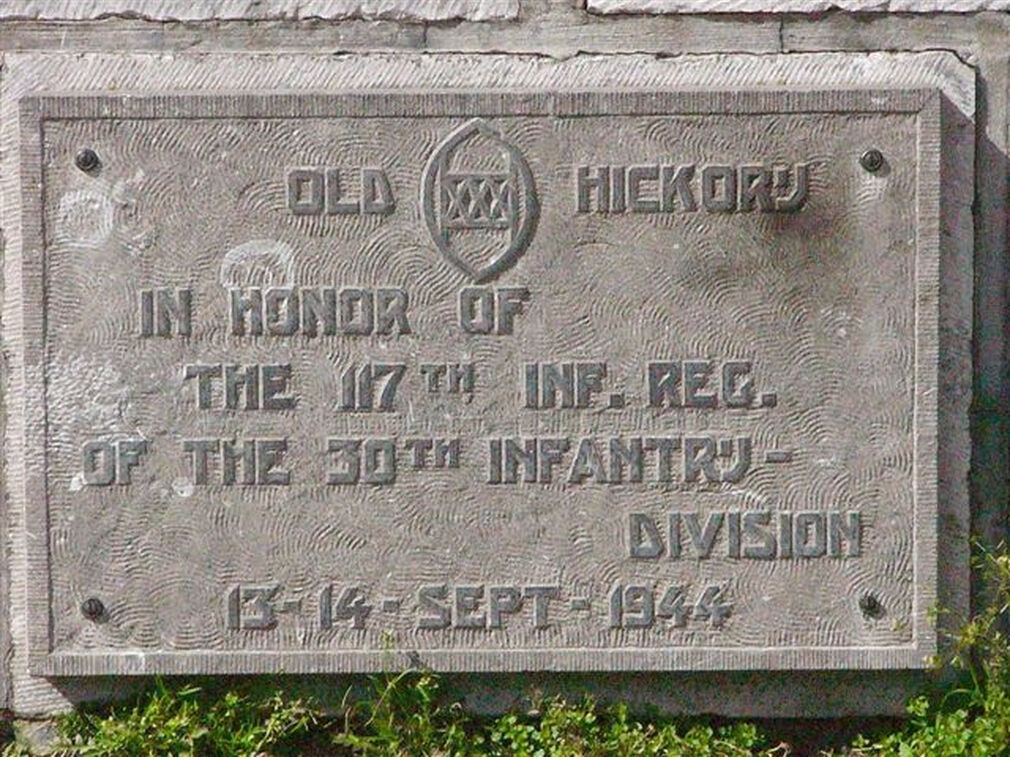

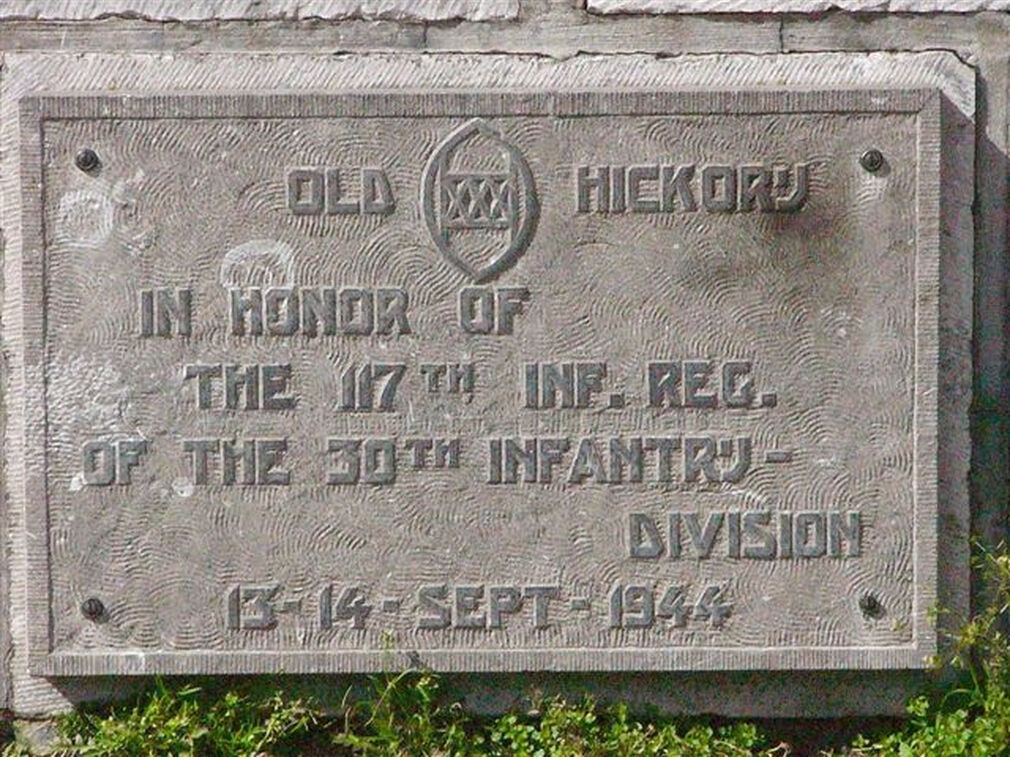

The Hickory freed ‘the Berg’ on 14 September and afterwards they sent us here to set up a supply route between the Belgian port of Antwerp and Aachen in Germany. We, the colored troops, were then stationed in "The Berg," at least part of us. When we finally arrived here and liberated the Limburg part of Holland, Frans and some other boys were still hiding in the surrounding forests. Some of them had been in the resistance, but Frans was too young for that.

His family lives in a house on the village border, but Frans usually sleeps in the Geulemer cave. He knows the cave system under and around "The Berg" as the palm of his hand. He played there as a child and, together with fellow villagers, took refuge during WWII's Battle of Valkenburg. Everywhere on and next to the road you can still see memories of that fight. Some houses are badly damaged and the ditches that people had to dig for them on the orders of the Germans are still there. After all those trips back and forth, I have my own landmarks: this ditch, that house. Like I said, "it started to feel too much like coming home."

It started to feel like coming home

If I can get a good piece of meat, I take it to Frans's house; his mother makes a nice meal out of it. They don't see much meat around here in those days. Keep the few chickens that are left over for the eggs. Frans ’mother is a sweet person. A great farmer's wife with six children. Her husband was rushed towards the German border with the first Americans. I have more or less adopted that family and make sure they have enough to eat.

Now that Valkenburg has been converted into a Rest Center by the army, we are getting all kinds of luxury goods that the farmers have not seen in years. We try to bring some of those extras to Frans's shop and we keep behind what we can get for "our" families. Almost all brothers support a family. You know, they looked at us a little suspiciously in the beginning. We knew from the talks that blacks would have a tail, like monkeys. But when we were here for a few weeks, we were overloaded with all possible Dutch friendliness.

And believe me, it is much more pleasant for us here than in Valkenburg where all kinds of rules apply to the colored soldiers. Where they can go and what they are allowed to do. There are separate shelters there for colored troops, a separate hospital and a separate relaxation area.

Here in "The Mountain" we have our own kitchen and sleeping space, but we can go wherever we want. I usually go back to "The Berg" after a ride instead of staying in Valkenburg. I would like to spend those few extra miles for it.

Henri Vanlandingham is alongside Jefferson Wiggins, the only African American veteran until now, who told about his stay in Limburg at the end of 1944.