Cor Linssen

Cor had a happy childhood and he didn’t mind looking different from other kids. He had a great stepfather, who to him was just 'pa'. The other father did not exist, because, as he tells it, 'that is purely biological.' In the family, he just got accepted the way he was - for all he knew.

Aunt Nel always wanted to have me close by, as if she wanted to show me off, even when she was dating. Her boyfriend was not amused.

Cor was aware of the stories about his birth. His pa, Gerrit Linssen, was from Buggenum, and his mother, Mia Tegelbeckers, from Roermond. Mom and Pa Linssen already had two children during the war and they were living with grandpa Tegelbeckers. Towards the end of the war Roermond was evacuated on German orders and Mia and her two children left for Budel in the province of Noord-Brabant, to go and live with friends. The rest of the family went to Friesland. Nobody knew exactly where Mr. Linssen was at that time. It was said that he was sent to a labor camp in Germany, like many men from the region. Later it was known that he had escaped the camp. The Germans were looking for him as he had allegedly stolen food to give to Russian POWs.

Cor: ‘Pa said those Russians hardly had anything to eat.’

After Roermond’s liberation, Linssen returned and worked for the municipality, working at the US Army depot by the barracks. Linssen often brought home African American friends from work. Later Cor learned from an friend of Linssens's - far too late to his liking - that his father knew his biological father. 'The two of them would sometime eat their lunch together'.

June 17, 1945, the Americans left Roermond and when Cor was born on March 4, 1946, it was clear that Cor’s father was an African American. Mrs. Bremmers, the midwife who assisted Mia had sent for the family doctor as she thought the baby looked a little yellow. Cor: 'I heard later that the doctor and the midwife exchanged knowing glances when they were examining me.'

Cor was a perfectly healthy newborn.

The family had trouble settling in Roermond. When Cor was six weeks old, they moved to Buggenum, to live with his pa's family. Mia felt uncomfortable with the attention she attracted walking with Cor in his pram. Later on the family decided to return to a ruined Roermond.

Cor's mother always had an excuse at the ready when people scrutinized the baby: 'He looks like one of our cousins in Swalmen who is also really dark.' In 1948, the family got their own home. Cor did not remember who had told him this, but when they arrived, a girl next door yelled: "Mom, next door they have a Black kid".

Mia invariably introduced her children as: 'This is our Huub, our Jo, my Cor, our Herman, and our Ben.'

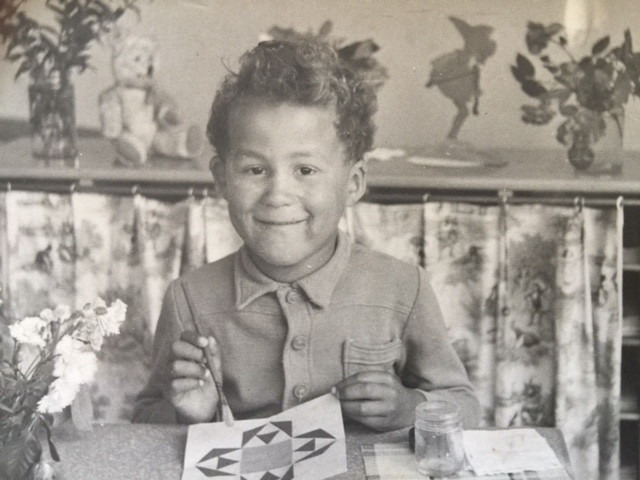

Little Cor was pampered by the female relatives and friends, in particular his aunt Nel. 'Aunt Nel always wanted to have me close by, as if she wanted to show me off, even when she was dating. Her boyfriend was not amused.' He allegedly once smacked Cor really hard. 'My aunt said: "You can't trust that one." Sometimes I was brought along when she went on motorbike rides with her suitor. She told me once she broke it off because of me.'

Cor did not mind all the attention. People often gave him treats, and liked looking at him. When he was about three, the family traveled to Buggenum to visit relatives, and they all went to the county fair. Cor enjoyed all the booths and the rides. He felt as if he could ride the merry-go-round for hours. Many people came by to look at him. The carrousel owner let Cor ride the attraction which drew a lot of customers to look. Cor did not mind when one woman came up to him and touched his hair.

In the local swimming pool, Cor was the only one with dark skin and curly hair. He was secretly proud to stand out. His skin contrasted nicely with his white swimming trunks. 'I was called "the black one", but the others got nicknames as well. The kid with the white hair was "cheese head", and the guy with the red hair was "the red bastard".

Many years later, people in Roermond still recognized him. 'Not surprising,' Cor said, 'since there were no other people like me in that city.'

From now on, just tell people, I got magic candy balls.

However, it gradually dawned on little Cor that there was something different about his ancestry. He remembered as an eight-year old, walking down a shopping street with his pa. He could see how people would look back after they had passed him. He sometimes asked his father how come he was dark. He father would answer, just like his mother before: 'You are mine, little fellow.' And that was that. Or was it? 'I remember a social worker, Mrs. Strijkers, sometimes talking to my parents in the parlor.'

When he was about eleven, his friends told him: 'We think you were adopted.' Cor decided to pluck up his courage and that night, when they were doing the dishes, he asked his parents for the first time why he looked so unlike other people. Because 'there is something different about me'. He still vividly remembered the scene. The reply was short. His mother told him: 'You are mine', but his father was silent.

While his pa would stand by Cor when he was boy, later on there was a reversal of roles and Cor the teenager would support his father, often with humor. He heard people ask his father how he had come by this dark-skinned son of his. Cor made up a funny reply his father could use: 'From now on, just tell people, I got magic candy balls.'

Reflecting on the past, Cor thought he only really became aware of his 'color' when other people of color started arriving in the city. In the mid 1960s, African Americans would frequent a bar where his older brother worked. They were AFCENT (Air Force Central Command) soldiers, stationed in Brunssum. Cor, then seventeen, worked at the bar earning pocket money rinsing glasses. He remembered that one of the soldiers always wanted to horse around with him. 'Hey Cor, want to fight?' Cor did not speak any English but he made do 'with his hands and feet.'

When he was nineteen, Cor decided to get into the hospitality branch and applied for a job with the Holland America Line. Cor did very well on board the ships and the passengers loved him and his beautiful smile. Once, a rich American woman gave him a 100 dollar tip: 'Cor, thank you for your one million dollar smile.'

His coworkers and the passengers often asked where he was from. 'I got fed up with those questions about my origin. So I started telling people I had been adopted.'

During his time sailing, Cor was not aware of racism. That changed when he called a clumsy coworker from Indonesia 'peanut cluster'. The coworker complained about it to the captain and Cor got reprimanded. He was not aware he had done anything wrong but it was how he learned about discrimination. Once, the ship moored in Savanna, Georgia. He was advised to stay aboard, and not go out because of the racial discrimination in the state. This was the first time Cor heard anything about racism in the United States. He ignored the advice and while waiting in line in a shop, he was scolded by a Black man. He had let an elderly white woman go ahead of him. That was not done. Cor had said "Where I come from, we let older people go ahead of us".

Cor had himself experienced discrimination, but it did not bother him. 'Even last year, when I was on a bike ride with my partner Truus, someone yelled "Foreigner!" at me. They probably thought I was Turkish or Moroccan.' Truus educated the man and made it clear Cor was a Limburger.

Cor's mother never gave him any information about his biological father. It was not until he was around fifty that he discovered that his father was an African American GI. At the time of the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation, there was a lot of publicity about liberation children.

Cor asked an old neighbor about his biological father, She replied: 'He was a gorgeous, dark, tall man who frequently visited your place at Knevelgraafstraat’. She did not know the name of this gorgeous man. 'So I know I descend from an American, but who it was, I don’t know.' Cor approached the TV program Without a Trace (Spoorloos), but when he told his mother, she said: 'If you do then I'll jump out the window.' Cor: 'Of course she was against it since she already had two children before I was born.'

Cor did not go through with it in order to spare his father and mother the publicity. Cor is now retired and has been living with Truus for over twenty years. They know each other as children. Truus remembered thinking that it was interesting that a Black boy could speak the local dialect. They both have two children from a previous marriage and a number of grandchildren.

Around the age of seventy, Cor started feeling tired and listless but could not think of an explanation. His family physician prescribed vitamin D which seemed to help. 'According to the doctor, it was because of my ancestors. People like me, with dark skin, often develop vitamin deficiency later in life.' Cor also turned out to have sickle cell anemia, an inherited disease prevalent in African American families. These days, he is doing much better.

Cor has told his story in similar fashion to Erick Municks, the author of Roermond during the War (Roermond in Oorlog).

http://www.roermondinoorlog.nl/oorlogsen-bevrijdingskinderen/bevrijdingskinderen/linssen-cor/ www.roermondinoorlog.nl/oorlogsen-bevrijdingskinderen/bevrijdingskinderen